Hortitecture: Architecture and plants as a shared system

Ms. Grüntuch-Ernst, you have published a book on hortitecture. What exactly do you mean by that?

The term hortitecture describes how architecture and living plants can be combined to form a system. It is a combination of the word architecture and the Latin word hortus, which means garden or park. Hortitecture is not about adding decorative greenery to buildings after they have been built, but rather about considering plants as an integral part of architecture and working together across professions to make this possible. This is because every building is not only its own internal ecosystem; the building envelope also has an impact on the urban space. Dark surfaces contribute to the heating of urban areas. Sealed surfaces prevent rainwater from draining away during heavy rainfall. If we understand the city in this sense as a coherent space, there is an opportunity to achieve a qualitative improvement through redensification.

As architects we need to think more about how our work is connected to other trades: landscape architects for example don’t just fill in the gaps between our building blocks decoratively. At Hortitecture, plants are part of the system. This makes it necessary to deal with substrates, wind loads, water management, maintenance and long-term development. It is not enough to simply place plants on a building. Ecological added value can only be created when many disciplines work together and contribute the necessary knowledge — anything else would be purely superficial.

A roof as a forest

You and your team at Grüntuch Ernst Architects have created an office building on Darwinstraße in Berlin, that puts the Hortitecture approach into practice. What does that look like exactly?

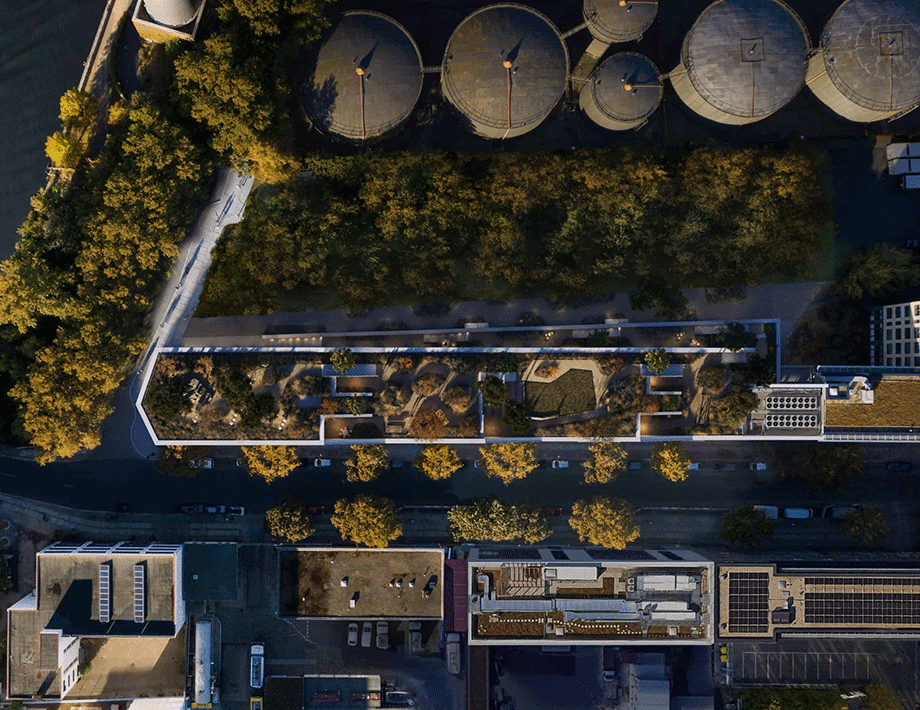

The building is a former power station in Berlin-Charlottenburg, consisting of a 110-meter-long structure that lines the street and extends to the Spree River. This setting inspired us to focus on the Spree area. At the head of the building, you have a 360-degree view over Berlin, but also into the depths of the Spree area. For a long time, the river was only seen as a transport route. We want to change that and use the building to promote its transformation into an urban space that can be experienced.

The office building has several entrances with small lobbies to allow for different uses. At the same time, there is a second access point: an open staircase that rises to the top via terraced steps resembling a garden. Together with landscape architects capattistaubach, we were able to design this space so that the garden is accessible from every level of the building.

The roof garden functions as a contemporary workplace: with large sliding doors, power outlets and Wi-Fi for working on laptops. At the same time, it offers space for informal encounters and regenerative breaks.

Can you describe the exterior of the building in more detail?

The model for the building and in particular the roof garden was the “Bosco Verticale” in Milan, where trees are planted in troughs on the balconies. We were not only inspired by the visual appearance of this building, but also learned a great deal from the technical implementation and choice of plants and trees.

The 2,200-square-meter roof garden is home to a total of five tree species and 35 plant species, which together form a dense biotope. To ensure that the plants on the roof survive and are not uprooted by a storm and blown onto the street, structural engineers calculated the load-bearing capacity and wind loads. The appropriate tree species had been grown in tree nurseries and prepared for their move, as they needed a compact root ball for successful re-establishment. The already tall trees were then lifted onto the roof with a crane and placed on planting chairs. These are steel wire baskets anchored in the concrete ceiling, in which the growing roots take hold. In addition, some trees are secured against storms by steel beams.

Interdisciplinary planning is required

That sounds like a considerable amount of additional planning work.

It certainly was. If you really want to green a building and not just decorate it with plants, you need a great deal of interdisciplinary knowledge. We had to bring together the knowledge of architects and landscape architects and also integrate additional expertise. The aim was to make the system as low-maintenance and resilient as possible.

In addition, unlike mineral building materials, plants grow and change over long periods of time. This also requires a different approach to design: instead of creating a finished building, Hortitecture involves relinquishing some control. Architecture is then no longer a finished state, but a process. This also changes one’s own attitude toward design.

What technical challenges had to be overcome?

Nowadays, the roof is often the place where all the building services are located. It doesn’t bother anyone there and the planning effort is kept to a minimum. However, because of the roof garden, we had to plan differently and instead accommodate the building services in a compact space within the building volume.

City and building in harmony

What effect do you want the building to have on the city?

Green spaces help cool the city and absorb rainwater. This way the building envelope improves the urban microclimate. The city should also benefit socially. With the publicly accessible roof garden we are giving a piece of space back to the urban community. Besides, the roof garden also offers added value for animals. In addition to numerous insects small animals such as foxes and raccoons find their way onto our roof. In winter, we have already found paw prints in the snow on several occasions.

In your opinion: Is hortitecture only an approach for selected flagship projects or can this thought also be applied to everyday urban development?

Hortitecture is not an exclusive concept for iconic individual projects. Of course, such buildings require a high degree of willingness to try new things

. But the underlying thought can certainly be transferred. The decisive factor is not the size or visibility of a project, but the attitude in the design.

When plants are understood as part of the architectural system other questions automatically arise: about the building envelope, water management and long-term development. This can also take place on a smaller scale. It is important to work in an interdisciplinary manner at an early stage and not to view greening as an add-on. Hortitecture does not necessarily mean more effort, but above all a different way of planning.

Biography

Almut Grüntuch-Ernst is an architect, professor, and member of the Berlin Academy of Arts. Together with Armand Grüntuch, she founded the Berlin-based office Grüntuch Ernst Architekten in 1991. Her work operates at the intersection of architecture, city, and landscape, addressing the question of how buildings can become effective as part of urban ecosystems. In addition to her architectural practice, she teaches at the Technical University of Braunschweig and is involved in research, teaching, and discourse on contemporary architecture and urban development. She has also published the book Hortitecture.